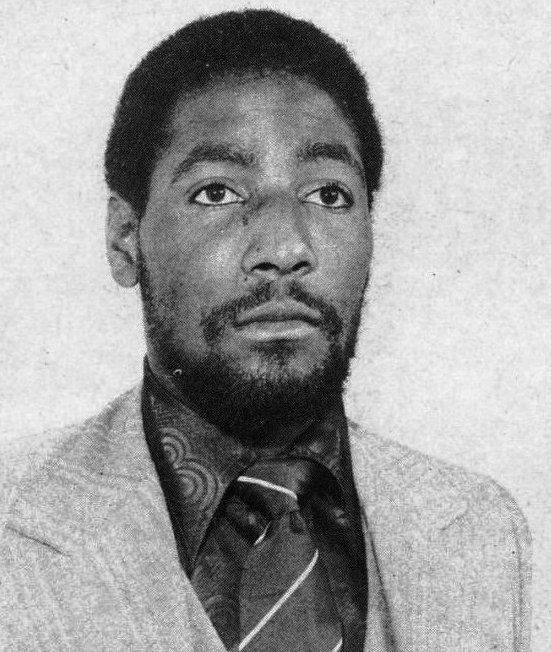

These days, Vivian Richards is a conquering hero. Many West Indian parents like to name their children with a flourish, and when Mr. and Mrs. Richards, of St John’s, Antigua, called the son born to them in 1952 Isaac Vivian Alexander, they gave him plenty to live up to. He calls himself Vivian— ‘the lively one’ — but this season he has really been more of an Alexander, a conquering hero; and I dare say the Isaac may come in useful yet, for many conquering heroes have ended up as patriarchs.

He first dawned upon the public in this country when he joined Somerset in 1974, though he had already had some successes playing for the Combined Islands in the Shell Shield, and against Denness’s touring team in the preceding winter, in his home town, he had scored 42 and 52 not out. Wisden wrote of the ‘immense gusto’ of his batting in this match. His first match for Somerset was in the Benson & Hedges Cup, at Swansea.

He reached 50 out of 89, was 81 not out when the match ended, and won the Gold Award. In his third Championship match, at Bristol, he made a century. He went in at 28 for 2 (soon to be 37 for 4) and scored 102, 70 of them in boundaries, out of 132. At the end of the season, he had scored 1223 runs at an average of 33. Eric Hill, never a man to throw superlatives around, described him in Wisden as ‘a wonderful phenomenon’, who ‘made the biggest impact of any player for Somerset since Gimblett in 1935’.

Yet there were those in Somerset who felt that, with all the talent he possessed, Richards ought to have scored many more (something which was, I remember, also said of Gimblett). They loved the hard-hitting, the daring strokes, and the general demeanor of laughing exuberance: but, they said, he sometimes takes risks when there is no need to, and gets out, and a match is lost which might have been won, or at least saved. Why sometimes he had even been known to laugh when he got out.

A drive that might have broken a window in St James’s Church (as one of Clive Lloyd’s once so nearly did) rises vertically and is caught by the wicketkeeper, after they have run one-and-a-half, and he laughs. Tain’t nothin’ to laugh about. But Somerset supporters have become a little bitter in the last few years. They will become their cheerful selves again once they have won something, even if it is only the Sunday League. With all these competitions, it becomes a slur if you do not win something, instead of a natural state of affairs, as previous generations of Somerset supporters had taken for granted.

Viv Richards went that winter with the West Indians to India and Pakistan. He did not seem likely, at the beginning of the tour, to get in the Test side, but Rowe had to with-draw at an early stage with eye trouble, and this gave Richards his chance. After failing in the first Test, he scored 192 not out in the second D. J. Rutnagur has said how, even in the course of this innings, it was noticeable that Richards matured in temperament and improved in technique against the spin bowlers. At the end of the tour, he was second in the West Indian averages in all matches, with 1267 runs at 60.

The 1975 season was, of course, an exciting season, but perhaps no special help to a young cricketer striving to develop, who was caught up in both its international and its county aspects. Richards did not, as it happened, do very well in the Prudential World Cup. For Somerset, he did better than the year before— 1096 runs, average 41— but not so dramatically better as they had hoped in Norton Fitzwarren and Nether Stowey. Then he went to Australia with West Indies, and into his year of glory.

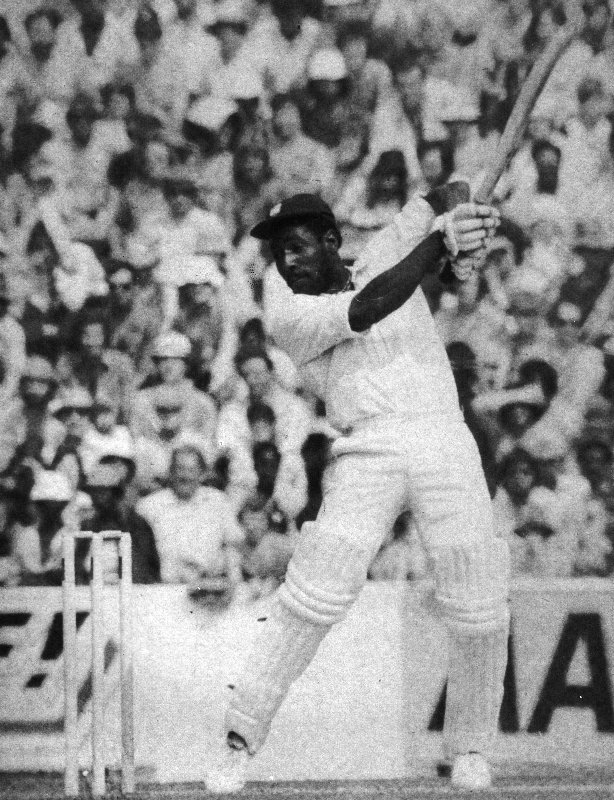

Since January 1, 1976, he has scored, in Test matches, against Australia, against India, and most recently against England, 1710 runs, which breaks the record for a calendar year (I do not much approve of this `calendar year’ records, a device by statisticians to provide themselves with more work, but there it is, not a figure to be passed off with a shrug). In the series against England, as you hardly need reminding, he scored 829 runs, missing one Test, with an average of 118.

Don Bradman scored 974 for Australia in England in 1930, with an average of 139, the only really comparable performance. Nineteen-thirty was a good, dry summer, but not quite such a batsman’s festival as this one. Bradman scored his runs against better bowlers (Larwood, Tate, Peebles) than England has had this season. I am not suggesting that Richards is another Donald Bradman.

But it says much for him that such a thought should cross our minds. What has happened to him? It is not, I think, that he has taken fewer risks, and become a little more cautious. No, it is that wider experience has enabled him to develop his technique, so that he can still take as many, if not more, risks — but has the ability to cope with them. He is as ‘exuberant’ a batsman today as when he first played for Somerset, but he plays better. No doubt later in life he will have to take fewer risks — even Bradman did. But he is only 24: he can cause much more havoc yet.

My colleague John Woodcock, the Sage, who has watched all the great innings of Richards this season, compared him to the famous ‘three Ws‘. ‘Frank Worrell was more elegant, Walcott more powerful, Everton Weekes was the most like Viv Richards of the three, though I doubt whether he hit the ball as hard: The best West Indies batsman of all, I suppose, was George Headley, if only because he had so much more burden to carry in the early days of their Test cricket. I was once discussing a World XI with Sir Learie Constantine.

We must choose George Headley first; he said, ‘and then we must choose Don Bradman, for he is the white Headley: One day we shall be discussing the great batsmen of the 1970s, and someone will say, ‘We must choose Vivian first, and then we must choose Barry because he is the white Richards.