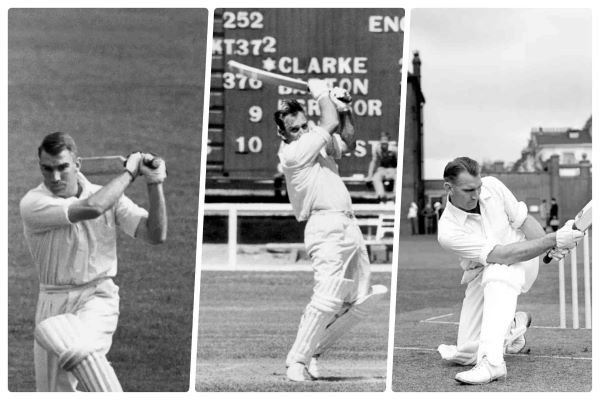

John Reid, the New Zealand skipper (1928–2020) and its finest all-rounder, knew only one way to play cricket: flat out. Everything he did was done wholeheartedly. Win or lose, he laughed and gave credit to his opponents. No fast bowler frightened him.

One of the features, if not the worst, of international cricket is the defensive. We must not lose attitude which has permeated and poisoned the game The West Indians have done much to dissipate this outlook, and laudably, England has emulated their example in Australia. Which is all to the good, for with so many other attractions, crowds will not pay to watch dull, negative cricket.

For years, John Reid of New Zealand has preached the gospel of attack, whether it brings victory or defeat. Crowds don’t flock to see winning sides that bore them, but they don’t mind watching losing sides that go all out for victory.

“Cricket is all attack,” says Reid. It is attack for the bowler, too, whether he is attacking through pace, spin, or any other of the arts of deception he employs. You know, it is an attack on the fieldsman, and above all, it is an attack on the captain.”

New Zealand is a country with a small population—less than two millions—yet they have produced teams that have held their own against Australian state sides and M.C.C. touring teams, and though they have won only half a dozen Tests, their men have given an excellent account of themselves. They have produced world-class batsmen in Dacre, Dempster, Martin Donnelly, Merv Wallace, Walter Hadlee, Blunt, Bert Sutcliffe, and John Reid, who is one of cricket’s great all-rounders. “What a pity,” a friend once said to me, “that John Reid was born in New Zealand on June 3, 1928, in Auckland; to what heights he would have risen had he been an Englishman or an Australian.

The converse might also be true. In England and Australia, he might have developed into merely another good all-rounder without his unique talents being brought to the surface. Because he has played for the weakest of all international sides, he has been spurred to do deeds he may never have achieved with powerful teams. He is a fighter—the type of man in whom adversity brings out the best.

As a leader, he inspires. Odds don’t daunt him. John Reid was fortunate for his ancestors. His father was a massive, rugged Scot, hewed out of granite, and one of the best rugby players in New Zealand. And rugby, rather than cricket, was John’s first love. Possessing unusual natural strength and speed, he did everything in top gear. Then, in 1943, he was thrown into a fierce rugby tackle. Rather than cricket, it was John Reid who went down with rheumatic fever, which kept him in bed the whole of the 1944 season. When he was well, he went at it again at full speed.

In one cricket match, he hit 189, of which 116 came within boundaries; in another, he took 9 wickets for 11 runs. He won sprinting and field events, the discus, and the shot, and he could project a cricket ball 120 yards. He smashed a boy’s nose in a boxing match, and the violence of the sport turned him off, leading him to conclude he was not cut out for it. In his final year, he represented the school in athletics, cricket, football, swimming, and as head prefect.

Post-War Giants:

John Reid wasted his energy in a prodigal manner and went down with rheumatic fever again. That finished him for rugby, and for months it was doubtful whether he would play cricket again, but the following season saw him rolling up his sleeves to bowl.

It meant the end of his chosen employment, however, for he intended to teach and specialize in physical education. In 1947, he joined the Hutt Club, for which he kept wicket, for there seemed no limit to his versatility. Hugh Duncan, a New Zealand selector, noticed that John Reid had amassed 1,000 runs over the season and suggested that he play in the Plunkett Shield Games. In his first innings he made 79 against Canterbury and fell on top of the world. Then, as often happens in cricket, he came down with a bump and made one in the second inning. No game ever invented can deflate the big-headed and the cocksure as cricket of the world, as often happens, though John Reid has never needed a bigger hat.

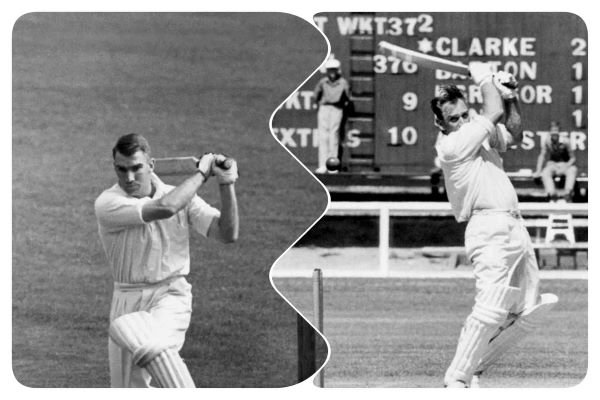

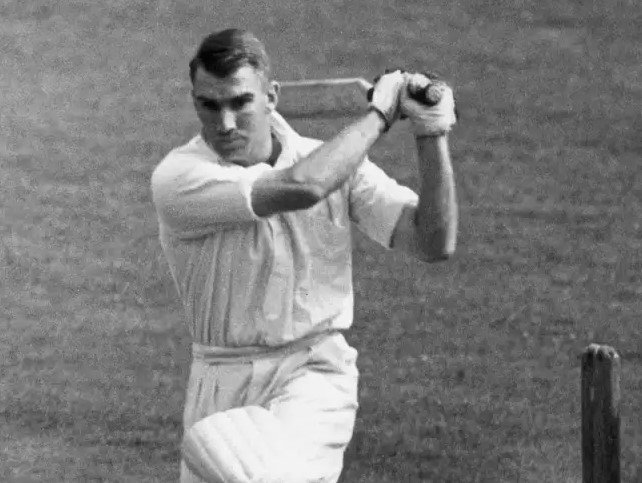

Young John Reid was very strong, with wide shoulders and a deep chest. He hammered the ball with every ounce of horsepower he could generate. One writer said: “Ife hits the ball with youthful fury,” and that is how he has always played.

“The very nature of my physical inheritance would have made it quite absurd,” says Reid, “had I played pat-a-cake with the ball. Yet I sincerely believe that had I been the veriest shrimp, my desire would have been to belt the cover off the ball.”

By Harvey Day:

Yet, how often does one see tall, well-built men who treat a cricket ball as if it were packed with high explosives? The ball is meant for hitting. All his life, he has been eager to learn. In one game, he and Ian Cromb put on 216 runs together, and Reid was 109 (not out) at the end of the day. Ian Cromb saw a fault in his driving, and they went to the nets the next morning to correct it. Apparently, the lesson was a success, for he added 107 runs to his score.

It was then that people started talking’ about him for the 1940 tour of England. He played no rugby in 1947–48, and the rest built up his physical reserves, so he returned to cricket in 1948–49 completely refreshed.

That year, Joe Hardstaff of Notts went out to New Zealand to coach and played for Auckland against Wellington. When John Reid faced the fast bowler like Jack Cowie, Joe Hardstaff, who was at silly mid-on, observed a weakness in his leg stroke, so between balls he muttered under his breath, “Get foot outside ball on leg stick.”

The next ball was on the leg stump, so he planted his foot outside the line of flight, and the ball whistled past Joe’s ear like a rocket. “Ee, that’s right, lad,” he said approvingly. It’s these little things that make the difference between a crude but promising bat and the finished product. He absorbed lessons so well that he found himself on the boat for England in 1949. There were veterans on the side from whom he learned:

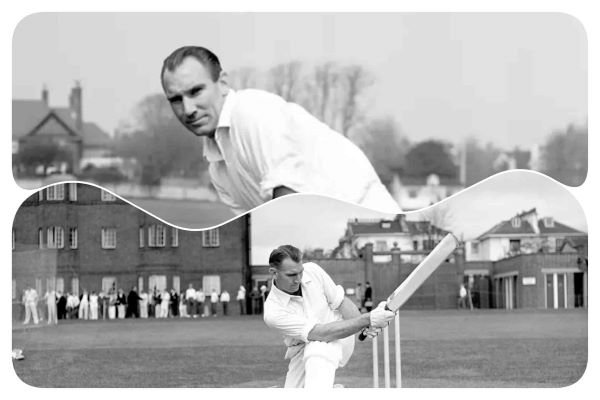

Merv Wallace, Martin Donnelly, Scott, and Hadlee. At Cambridge he made his first century of the tour-188 (no.) One critic wrote: “Reid hit with tremendous power towards the end and hit 23 fours.” Swanton remarked: “Reid’s batting is built around sound principles, and his instinct is to hit the ball hard and often.”

With such rich batting talent, he did not get his Test chance until Manchester, where he made 60 and, in company with Martin Donnelly, added 116 runs. In the second inning, he made 25 before Bailey got him. It was a fine experience, and his fielding caught the eye of the critics. – E. W. Swanton said: “A new asset appeared in Reid’s fielding at mid-off. He stood there all day to Burtt, cutting short every manner of hit of whatever power, and I have not seen anyone quite so good in the position since Bradman was young,” which was indeed high praise, for Sir Don Bradman was one of the greatest outfielders ever.

Against the Northants, he made 107 (no.) and 72; against Warwick, 151 with 22 4’s. Against Notts, he and Ra-Bone put on 246 for the third wicket, his share being 155. In the final Test, he kept wicket in place of Frank Mooney, who was injured, then went in at No. 3 and was LBW in trying to hit a full toss from Wright out of the ground. In the second inning, he made a glorious 93 while fighting to avert defeat.

John Reid played in two of the four Tests and ended with an average of 43.25, standing fourth after F.B. Smith, Donnelly, and Sutcliffe. In all first-class matches, Donnelly, Sutcliffe, and Wallace had better averages. The first two topped the 2,000 mark: Merv Wallace got 1,722 and John Reid got 1,488 runs. As the side was rich in bowling, he was given only 127 overs and took 13 wickets for 30 runs apiece.

The 1949 tour was New Zealand’s most successful English tour, and Wisden mentioned “the batting of 21-year-old Reid, who made the great advance. Long before the end of the summer, Reid was established as the leading all-rounder. Learning rapidly from experience, he improved his batting by adding solidity to his punishing strokes. He was always the best of a superb fielding side, showed himself a good deputy in the Test for the injured Mooney, and though Hadlee resisted the temptation to use him much, he could deliver as fast a ball as anyone in England at that period.”

Reid has always been at his best against really fast bowling, and it was on the hard strips of South Africa that he scintillated. During the 1953–54 tour, he started against the Western Province with 8 and 11 and followed this against the Eastern Province with 51 and 2. As his next scores were 15 and 2, the South Africans felt they had gotten his measure. In fact, the New Zealand team had been written off before the tour started.

In the game against Transvaal, he hammered the ‘unhittable’ Tayfield mercilessly, and when Jackie McGlew took him off, Hugh Tayfield remarked, “Skipper, isn’t it amazing how a chap can shut his eyes and swing at anything and everything? Next time he’ll open his eyes, and then I’ll bowl him.” That day, he shut his eyes’ and belted the South African bowlers for 175. In the third test, when N.Z. scored 505, his share was 135 in the two hours between lunch and tea. In the fifth, he made 19 and 73 and ran out.

In 1961, John Reid traveled to South Africa and determined that his men would play bright, aggressive cricket and prove again that Mr. Tayfield could be put in his place, even if it had to be done with shut eyes. Whatever else happened, they were determined to hit South Africa’s finest off-spinner. And they did. In their first innings against him, Hugh Tayfield took one for 82; in the second inning, he took one for 50; and never again did the selectors consider him for Test matches.

At Newlands, Cape Town, against Western Province, N.Z. made 523, of which Reid scored 203 in 221 minutes and hit 25 fours and four sixes, after which Herbie Taylor wrote: “In John Reid, the New Zealanders have a player in the Wally Hammond and Dudley Nourse class. The most important feature is that Reid’s shining example brings out the best in the Kiwi players. His presence in the side makes a difference to the tour and draws the crowds in the same way as Wally Hammond, Denis Compton, Frank Worrell, and other world-class batsmen.’

New Zealand lost the first and second Tests despite some excellent batting, particularly in the second inning when Graham Dowling got 74 and 58 and John Reid got 39 and 75. Moreover, in the third test match, South Africa, who made 190 and 335, was outplayed played New Zealand. They won the toss, batted first, and made 385 and 212 for 9. The major contributors were Harris 101 and 30; John Reid 92 and 14. It was a grand day for New Zealand.

South Africa won the fourth test match in Johannesburg and clinched the series. South Africa scored 464, to which New Zealand could reply with only 164 and 249, but the match was a good for captain John Reid, who scored 60 (10 fours and 84 minutes) and 142 (21 fours and 2 sixes, 259 minutes). Though New Zealand were defeated by an innings and 51 runs,.

In the final Test at Gqeberha, New Zealand scored 275 and 228 and South Africa only managed to score 190 and 273. Paul Barton made 109 and 2 for New Zealand, and John Reid scored 26 and 69. New Zealand won the match by 40 runs. John Reid’s consistency was astonishing, especially as he bowled a great deal at a great pace and headed the Test bowling averages.

His personal example inspired every man in the side, and he made more runs on tour in South Africa than any batsman, English or Australian, before him! His tour aggregate was 1,195, and his average was 63.39. In tests, he made 546 with an average of 60.67. Like all great players, though, his achievements are incalculable; he inspired his youthful team to perform better than they had previously.

His final tour before retiring was to Britain in 1963—the first of the abbreviated tours granted to the minor countries in the international class: New Zealand, India, Pakistan, and South Africa. His side was unlucky to arrive during the wet test as half of the wettest summer within living memory, and the New Zealanders—all very young—were at sea against spin and failed to shine in mud and water.

They gave it their all, none more so than Reid, whose back condition prevented him from moving freely. He and his men gained unstinted praise for the way they played and the spirit with which they accepted defeat.

Wherever he has been, Reid has delighted the crowds with his lusty hitting, and in 1963 played an innings in first-class cricket in New Zealand in which he scored the record number of 15 sixes! He is the type of crowd that queues up to watch because they know they’re going to get their money’s worth.

In 1958, he narrowly missed making the fastest century during the English summer when he reached 99 in 86 minutes, then lost the strike for nine minutes, and eventually got his century with a six, which smashed a window outside the ground. No one has played harder and in a better spirit than John Reid of New Zealand, which must be a very satisfactory note on which to retire.

| John Reid Stats: | ||||

| Tests | ODI’s | FC | ||

| Batting | ||||

| Matches | 58 | 102 | 246 | 249 |

| Innings | 108 | 42 | 418 | 153 |

| Not Out | 5 | 11 | 28 | 25 |

| Runs | 3,428 | 282 | 16,128 | 1,575 |

| Highest Score | 142 | 64 | 296 | 69 |

| Average | 33.28 | 9.09 | 41.35 | 12.30 |

| Balls Faced | – | 377 | – | – |

| Strike Rate | – | 74.80 | – | – |

| 100’s | 6 | – | 39 | – |

| 50’s | 22 | 2 | – | 7 |

| Sixes | 33 | – | – | – |

| Catches | 43 | 30 | 240 | 81 |

| Stumps | 1 | – | 7 | – |

| Bowling | ||||

| Tests | ODI’s | FC | List A | |

| Matches | 58 | 102 | 246 | 249 |

| Innings | 72 | 102 | – | – |

| Balls | 7,725 | 5,473 | – | 12,662 |

| Runs | 2,835 | 3,034 | 10,535 | 7,074 |

| Wickets | 85 | 142 | 466 | 343 |

| Best Bowling Inning | 6/60 | 5/26 | 7/20 | 8/21 |

| Best Bowling Match | 6/60 | 5/26 | 8/21 | |

| Average | 33.35 | 21.36 | 22.60 | 20.62 |

| Economy | 2.20 | 3.32 | – | 3.35 |

| Strike Rate | 90.80 | 38.50 | – | 36.90 |

| 5 Wickets | 1 | 1 | 15 | 3 |

| 10 Wickets | – | – | 1 | – |