Mansoor Ali Khan Pataudi was a former Indian cricketer and captain. His full name was Nawab Muhammad Mansoor Ali Khan Siddiqui Pataudi also known as Mansur Ali Khan or M.A.K. Pataudi, and his nickname is Tiger Pataudi. He was born in Bhopal on January 5, 1942, and died on September 22, 2011, at the age of 70.

Those were the days of disappointment, the years of grief. The Indian cricketers just would not gel as a combined unit. The team spirit was at a discount. Parochialism and prejudice have ruled the roost, and the country’s cricketing reputation is in tatters.

In the winter of 1958, Gerry Alexander’s West Indies literally floored us, and in the following summer, in England. Peter May’s team massacred us with the utmost contempt. A drab, drawn series against Pakistan at home exposed India as the bulldogs of international cricket.

Not only was India incapable of winning a single Test match, but worse still, the mental attitude of the players seemed to border on negative thoughts and self-interest ahead of the team’s cause. However, the winter of 1961 brought about a refreshing transformation. All of a sudden, the Indian cricketers seemed to have acquired springs on their feet.

Even their appearance changed. Those stodgy, grim faces gave way to relaxed smiles. Ill-fitting clothes made way for sartorial elegance. At last, the Indian cricketers looked confident enough to rub shoulders with the very best. Gone were the days when they appeared distinctly uncomfortable and suffered from inferiority complexes.

But how did such a radical change take place? Primarily because of the advent of one man who was destined to lead India into an era of freedom from submissive self-consciousness? Bhopal, Winchester, and finally Oxford gave us the ‘springing tiger’ in the form of Mansoor Ali Khan of Pataudi.

He, at the time still the Nawab of Pataudi, brought about a discernible difference to the attitude in the Indian dressing room. Men like Jaisimha, Prasanna, Budi Kunderan, Farokh Engineer, and Hanumant, among others, found their voice and gave full vent to their personalities.

With Polly Umrigar playing the paternal role to perfection, Borde lending his solidity, and the genius Salim Durrani his fluidity, the Indians finally began to play handsome cricket. They brought about Dexter’s downfall at Calcutta and Chennai (then Madras), enabling India to record her first series victory over England.

Mansoor Ali Khan Pataudi was, of course, not the captain of India at the time. That was only his debut series in international cricket. But such was the influence of his mere presence that men far more experienced than him began to develop confidence in their own abilities. Pataudi did not know thralldom; he did not know submission.

He had played against the best in their own backyard on their own terms and proved himself to be in the top bracket. Consequently, his manner and mien were of self-assurance, and fortunately for Indian cricket, he had the aura to permeate that self-assurance into others.

The 1962 tour to the West Indies was an unmitigated disaster throughout. After skipper Nariman Contractor’s most unfortunate head injury in the Barbados match following the second Test,. Mansoor Ali Khan Pataudi, the fledgling vice captain, was thrown into the deep sea.

With Polly Umrigar’s assistance, he somehow survived the ordeal of Frank Worrell’s marauding men and returned to India, more mature than his 22 years of age. Now he was in the saddle. Almost overnight, he was thrust onto it by circumstances beyond control. Therefore, he tried to maintain a cool, almost casual exterior.

It was apparent that the slight hump was a little more pronounced. The responsibility and the care of leading a team of diverse tastes, habits, languages, likes, and dislikes can either make a man a hero or throw him deep into a chasm.

None yet; not even C.K. Nayudu or Lala Amarnath had handled the Indian team with any sense of unity, although it must be readily admitted that Polly Umrigar was the one who came closest to being the real leader of this diverse group.

Now it was the young Pataudi’s turn. Sheer perception helped him to fathom the problems of captaining an Indian team. He brought about a delightful change, and he did not demand respect; he sought to earn it through personal example on and off the field.

Most importantly, he kept himself far above petty considerations like regionalism and class bias. A leaf from the approach introduced by Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose and his I.N.A. men. By Indian sports standards, this was a distinctly novel idea—a giant leap forward indeed.

Unfortunately, we have gone many steps back ever since he left the scene. Earlier, very few of the Indian captains had been selected on merit. Most were appointed because of their proximity to the powers-that-be. They led by rote, using all the prejudices prevalent to keep the establishment happy.

That was surely no leadership. Just a vehicle to carry out the orders of men in power, who pulled the strings from the background to satisfy their Pataudi, had no need for cricket managers in his time. Actually, he would have considered such an appointment an affront to his mental faculties’ petty considerations.

Mansoor Ali Khan Pataudi’s presence and personality changed all that nonsense. He had an aura that kept the sycophants at bay and had no time for regional politics or for class bias. Tiger MAK wanted to enjoy playing cricket and knew well enough that to enjoy it, one had to try one’s utmost with the best available talent.

He appreciated the players’ intrinsic worth. Inevitably enough, the Indians developed self-respect and were making headlines across the globe, playing positive cricket, and most importantly, winning matches. No one dared to call the Indians’ dull dogs anymore. Pataudi was a revelation.

In appearance and inability, he exuded confidence. His distinctive style sent a whole generation into trying to emulate him. The man was an inspiration to his fellowmen and a much-admired person to his opponents. Cool, composed, and confident, the cricketer in him had a cavalier panache.

He brought back the adventure of our days on Nayudu and Mushtaq Ali as he lofted the ball over the heads of fielders with the utmost nonchalance. It was he who revolutionized fielding among our players through his own lofty deeds. Conditions and reputations never ruffled him.

Moreover, in his only series in England in 1967, he was superb at Headingley, with scores of 64 and 148. After that, he was also on the tour of Australia, where, despite an injured limb, he batted brilliantly to score 75 and 85 at Melbourne. His batting was based on sound technical principles, but he never allowed the technique to dictate to him.

He would innovate; he would evolve on his own to overcome the problem of impaired vision in one eye. Therefore, it was the result of a car crash in England before he had made his Test debut. His only tour of the West Indies was unsuccessful in terms of runs.

But the baptism by fire made him mentally tough, and he was quick to grasp that international cricket was a totally different ball game to the English county scene, of which he was a part with Oxford first and then with Sussex. Moreover, Tiger relished challenges.

The tougher those were, the more the phlegmatic man dared to combat it. On Indian wickets where the pitches were favorable to batsmen, Tiger was not always at his best. He gave the impression that he could not motivate himself in matches that descended to a dreary end.

Appeared listless, withdrawn Pataudi’s Test aggregate of 2,793 runs at a decent average of 34.91 includes six centuries, the highest being 203 not out against England in 1963-64. On his only tour of England, he scored 269 runs at 44.83, and on his only tour of hardships, he was a man inspired with 339 runs at 56.50.

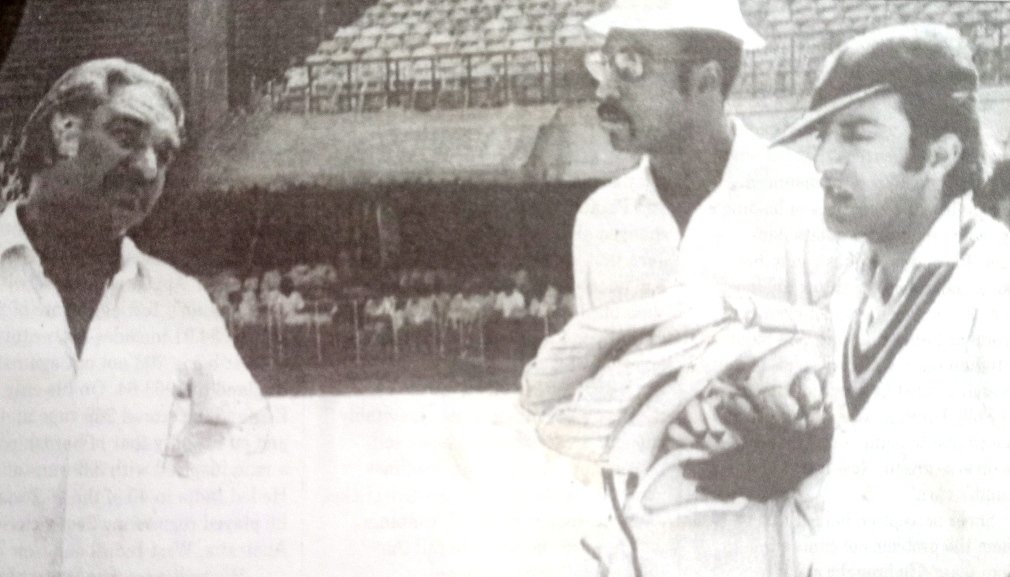

Mansoor Ali Khan Pataudi led India in 40 of the 46 Tests that he played, registering Test victories over Australia, the West Indies, and New Zealand. His brilliance as a leader of men came to the forefront time and again. However, none more so than at Calcutta in 1974-75 against Clive Lloyd’s men.

At the time, he was well past his prime as a batter and was brought back with the might of Gordon Greenidge and Viv Richards, Alvin Kallicharran and Clive Lloyd, Buberta, and Keith Boyce. The first two tests were lost, and in the third test at Eden Garden, the stage was set for the West Indies to give the final punch.

But Tiger and his young Indian team caught the daunted West Indies men by their neck. Gundappa Vishwanath played the stellar role with a supremely authoritative century, and Pataudi’s 37 after being laid low by a riser was an inspiration to his mates.

On the final morning, when Clive Lloyd and Alvin Kallicharran were going great guns to bring off the deciding victory of the series, Tiger did not relinquish his faith in Chandrasekhar. He knew if anybody had the capability to run through, it would be the unorthodox spinner.

Initially, Chandra came in for some punishment, and Eden roared in disapproval of Tiger’s insistence on Chandra. It took much courage to withstand that kind of public, but his gamble paid off as Chandra went through the defense of Lloyd and Kallicharran.

Then he brought on Bishen Bedi, polished off the tail in next to no time, and left the field with splendid reserve. No hugging, no high-gives, no vulgar gestures—just a wry smile and a pat on the back for Bedi and Chandra. Bedi and Chandra knew what that pat meant. So did the connoisseur.

The crowd was on its feet in joy. They wanted the tiger and his heroes to run a victory lap. But the tiger in him would not subscribe to such common dictates. He came out of the pavilion, stood at the gate, waved once, and vanished forever. On the next test, too, the Tiger magic worked.

This was Tiger Pataudi at his best. He was a man of perception who understood and nurtured brilliance. It was under him that most of India’s prominent cricketers of the 60s and 1970s came into the limelight. Gundappa Vishwanath, Bishan Singh Bedi, Chandra, Prasanna, Venkataraghavan, to name a few, had no need for cricket managers in his time.

Actually, he would have considered such an appointment an affront to his mental faculties. He would most certainly have said, “If the cricket captain cannot make cricketing judgments and cannot take cricketing decisions, why is he there in the first place?” So would have C.K. Nayudu, Lala Amarnath, Polly Umrigar, and Sunil Gavaskar.

But Tiger Mansoor Ali Khan Pataudi for all he’s worth and his contribution, could have been a little more committed. If he had only put his foot down a little more firmly at times, many of the evils of Indian cricket would have died there and then.

For the tour of Australia in 1968–69, Desai and Kulkarni were selected, although neither was named for the final 30 camps at Pune! That was a travesty of fair play and justice. But Tiger’s stiff upper lip remained so. If only he had twitched his nose just once, both Bedi and Gavaskar would have been spared the duty of cleaning the Augean stables of Indian cricket.