The moment you sit down to write about Rohan Kanhai, the mind is suddenly flooded with words more commonly associated with wild violinists or extrovert conductors: mercurial, improvise, cadenza, virtuosity, panache, and elan.

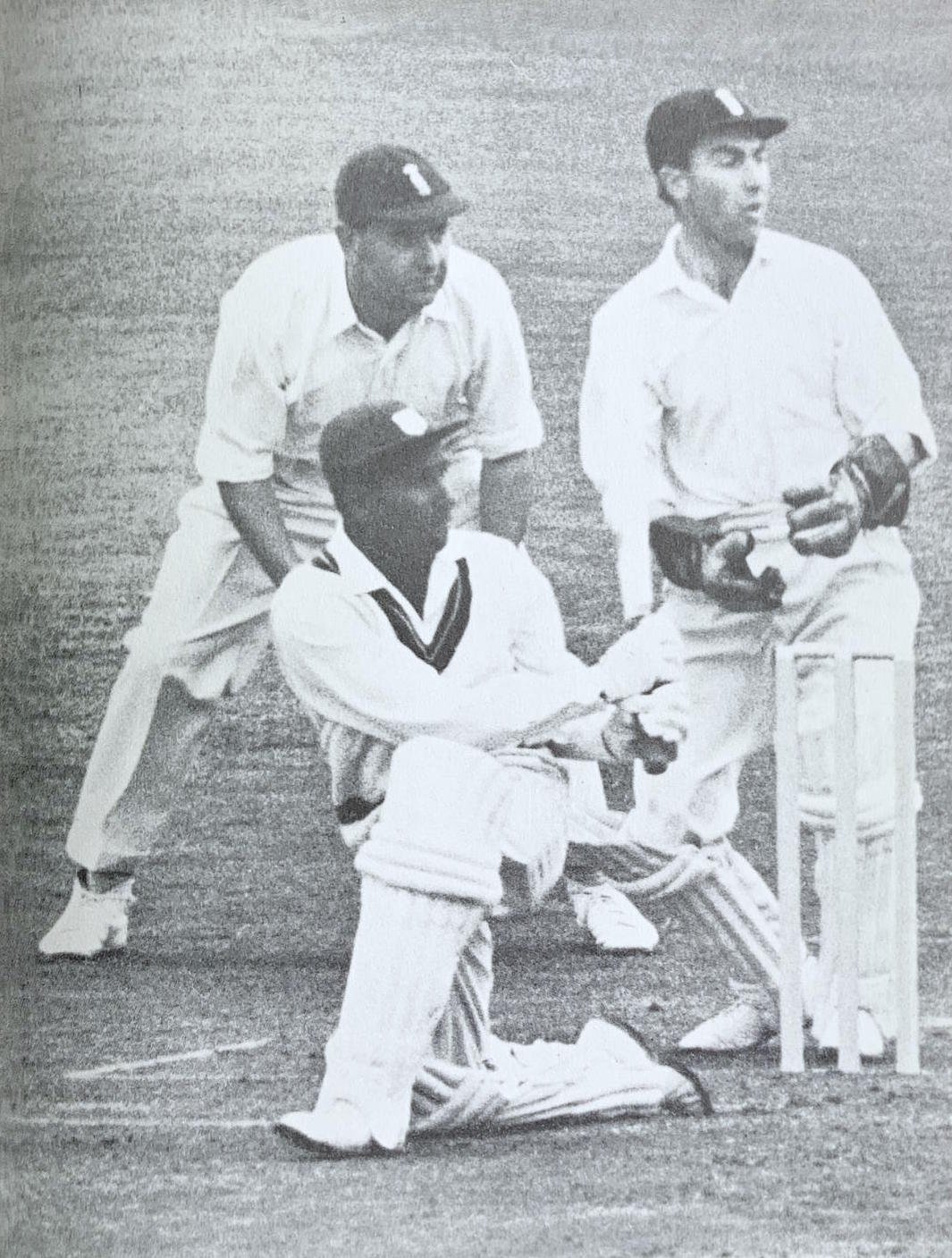

They are dramatic words, and they are justified, for Kanhai is a batsman of theatrical brilliance. Indeed he is the inventor of the one truly original shot to be added to the great art of batsmanship in the past 20 years. Confronted by the problem of hooking enormous bouncers from very fast bowlers, not easy when you stand only 5 ft 7 in (1.70 m) in your cricket boots, he devised a method of vertical take-off and mid-air spin that positioned him to play a copybook overhead smash of the kind Laver plays so well at Wimbledon.

Missed: Occasionally he missed. Mostly he connected. Always he finished flat on his back in the crease with the dust clouding up around him. Kanhai’s ‘falling hook,’ which was as close as any of the cricket writers could come to describing it, was hardly the most elegant stroke known to the game. It lacked the majesty of Hammond’s cover drive, the imperiousness of Ted Dexter’s straight hitting, and the glittering sober flash of a Harvey square cut. It had the virtue, however, of personifying exactly Rohan Kanhai’s tempestuous character. He played it perhaps a dozen times in the Test series in England in 1963 and even more frequently in lesser matches. It is a matter of some significance, therefore, to record that he has played it only twice in the past four years.

I know I was tempted once in 1969 and couldn’t resist it,” he said. “The other time was at Trent Bridge last season.” Since then Rohan Kanhai has been elected to captain the West Indies in succession to Gary Sobers, a feat few could ever see him attaining. The significance, in his own words, is that he has ‘steadied up.’ “Cutting out shots like that,” he said, “is all part of a cricketer’s education.” It is also, I suspect, the result of slowly emerging from the massive shadow of Gary Sobers. Kanhai no longer has to command attention by outrage. He is now recognized as what he has been for 10 years: a genius. Of an innings he played at Gravesend in 1970, Colin Cowdrey said, “No other batsman living could have played it.”

It was not only a masterpiece but an original masterpiece.” Like Gary Sobers, Kanhai’s art owes nothing to formal coaching. He learned to Kanhai, climbing into a towering drive. He plays without pads or gloves on a fast wicket on a sugar plantation in Guyana. He emerged into top-class cricket with the build of a flyweight boxer, the wrists of a fencer, and the footwork of a dancing master. But there, already, was his near-contemporary, the great Gary Sobers. The rivalry was unspoken, but it was there just the same, and it is revealing to check through the records and see just how few major partnerships they played together.

Temper: Perhaps it was this that added to Kanhai’s ‘unpredictability’ off the field as well as on it. He had a temper and sometimes showed it. Sometimes, around midnight, he could be decidedly undiplomatic. It was at such a witching hour in Barbados, on one occasion, that I saw him taunted into a typical indiscretion. We were at a private party at which an American baseball player of meager reputation demanded to know how much money Kanhai earned a year from cricket. “And you’re a star,” scoffed the American when Kanhai finally told him. I earn twice that in the taxi squad (reserves). Rohan Kanhai, who was not out overnight with perhaps five or six runs to his credit, prodded the American in the chest and took a very large bet that he would make a hundred the following morning. The next day he was out, blazing, without adding a single run to his score.

Nor would he have taken the bet. Nor would he have been goaded. “You learn these things,” he says, “but with some of us it takes time. He is essentially no different a cricketer now from what he was 10 years ago. He is merely a better cricketer, despite a series of injuries that threatened his career.

The game,” he says, “is one continual education. As long as your eyes hold out, you learn all the time. But that education doesn’t really begin for any player until he has come to England. Here you have to play under all conditions, on all types of wickets, against really professional players. It is here you learn discipline both as a batsman and a man.”

The discipline has added not only years but also distinction to his volatile career. Last winter he took over the captaincy of Guyana and led them to their first championship in the Shell Shield. They followed, at the official age of 36, your quote, but you refused to refute the record book. Rohan Kanhai smiles when the captaincy of the West Indies is mentioned.

He does not inherit, as Gary Sobers did, one of the great panzer divisions of Caribbean cricket. But it is his fortune that his younger batsmen, like the Gordon Greenidges, Lawrence Rowe, and Alvin Kallicharran, have all served their apprenticeships in English cricket. Much, though, still rests during the second half of this summer on the maestro himself. After years in the wings, the soloist is in charge of the orchestra.

By IAN WOOLDRIDGE SPORTSWEEK, July 8, 1973