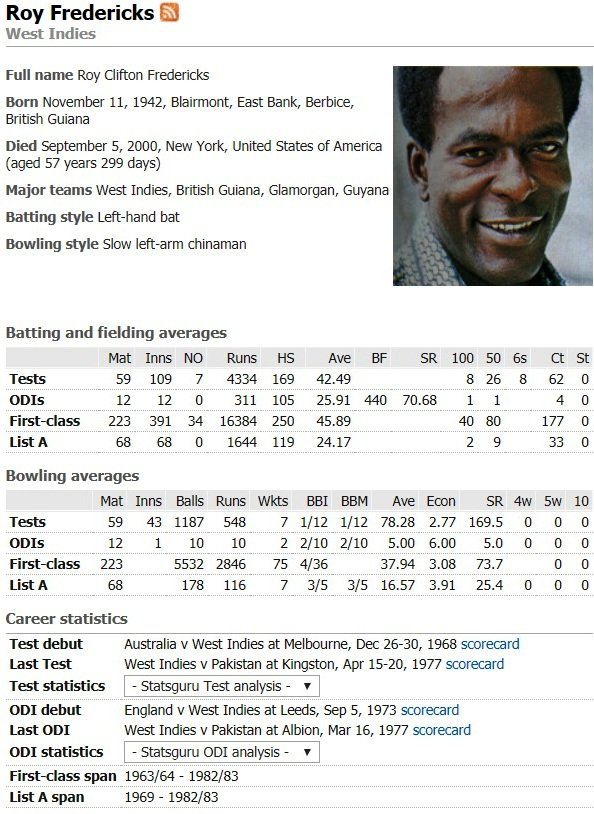

Roy Fredericks was 57 when he died of throat cancer in New York on September 5, 2000. West Indies cricket is always in dire need of that, legend Roger Harper said on his death. Fredericks was born and raised in Blairmont, a sugarcane farming community in eastern Guyana. He played in 59 Test matches for the West Indies, scoring 4,334 runs and averaging 42.49 runs per inning with eight hundred.

Roy Fredericks Memorable Century

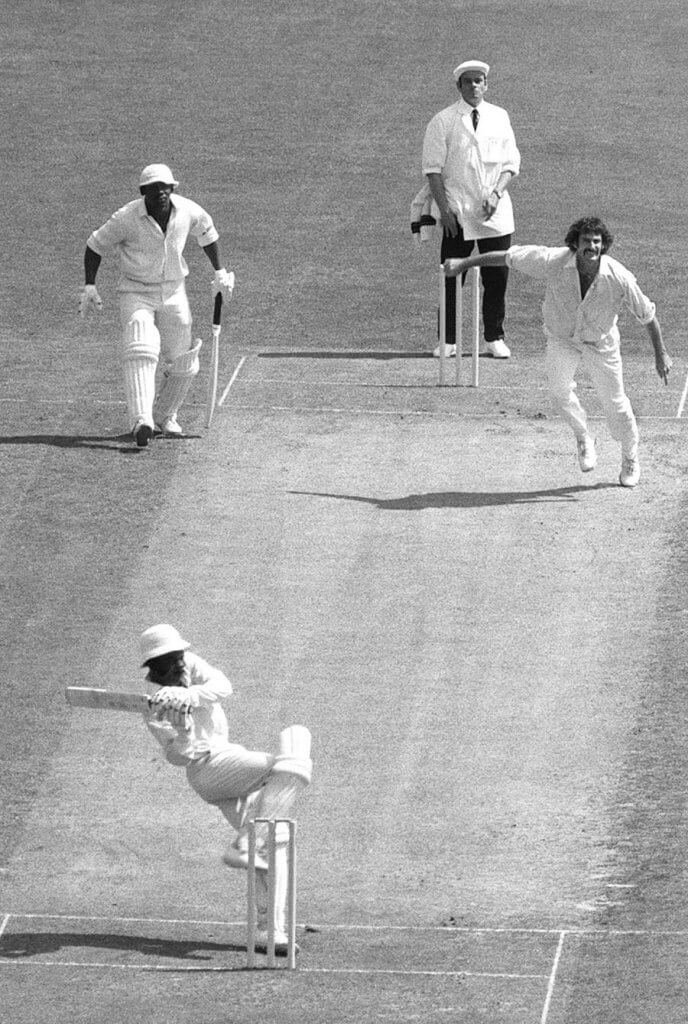

He was most remembered for the 169 runs he made against the mighty Australian team during a 1975–76 tour. When he was rattled off a century in just 71 balls before the lunch interval, the knock included 18 fours and a six struck off the day’s second ball, and it lasted for three hours before he was dismissed. Several former test players were present at the funeral. This fine left-hander from Guyana displayed an adventurous approach to opening the batting, and his cavalier stroke play delighted the crowds.

He loved to hook the fast bowlers and was equally strong on the offside with power cuts. Although he prefers the aggressive style, he could adapt his methods and play defensively if required. Initially, he was uncomfortable with top-quality spin bowling. He adapted his methods to become more than competent in dealing with the slower bowlers, although he always favored pace.

Roy Fredericks was a short man, 5.6” like many, who played the hook well. He was also a useful occasional slow left-arm bowler and a good close-in-the-wicket fielder. He was part of the 1975 World Cup-winning team, memorably dismissed in the final when he hooked Dennis Lillee for six only to dislodge a bail. Roy Fredericks made his Test debut on the West Indies tour to Australia in 1968-69 and was a fixture in the West Indies team until he joined Kerry Packer’s World Series Cricket team in Australia in 1977–78.

He continued playing for Guyana until retiring at the end of the 1982–83 season. He had a successful English county career with Glamorgan, playing for them from 1971 to 1974. After his retirement, he followed a career in politics, serving as Minister of Sports in Guyana as well as being a West Indies selector.

Struck with throat cancer in 1998, he sought treatment in the USA. He hit eight Test hundreds and 26 fifties, in addition to catching out 62 batsmen. As a bowler, he took seven Test wickets, but at an expensive 78.28 runs apiece. In 12 one-day internationals, Fredericks totaled 311 runs at an average of 25.91 with a century against England in 1973 in the only second match.

A Very Hard, Uncompromising Cricketer

Former West Indies fast bowler Colin Croft paid tribute to Frederick on the website Cricinfo: There must be something special planned elsewhere. Over the last few years or so, not only did the West Indies lose some special fast bowlers, including Barbadian quickies Malcolm Marshall and Sylvester Clarke and Trinidadian Jaswick Taylor, but Barbadian opening batsman Conard Hunte also left.

Even before that, another Guyanese, Clifford McWatt, a wicketkeeper, also went to the playing fields elsewhere, just following the departure of Barbadian all-rounder Keith Boyce. Could it be that somewhere else, outside our world, another West Indies cricket team is being configured and reunited for some special appointment?

No Guyanese, nor indeed, no regional West Indian cricketer involved in the late 1960s and early 1970s, would not have met Freddo. When he had just come to the regional scene, around 1966–67, from Blairmont Sugar Estate on the West Bank of the Berbice River, he formed a very valuable, productive, and lasting partnership with Steven Camacho, who, incidentally, had just retired from the position of Chief Executive Officer of the West Indies Cricket Board.

Between them, they generally murdered the bowling, especially fast bowling from every country in the Caribbean. That the two actually played Test cricket was not surprising at all. Many of us went through high school suggesting, when we batted, that we were Fredericks, Camacho, Clive Lloyd, Rohan Kanhai, or Kallicharran. To us as schoolboys, these names were legends. For me to have played either with them or against them in some form of proper advanced cricket, even in Test cricket, was a bonus and especially a special treat.

One thing was immediately obvious to us youngsters. Freddo feared no fast bowler around, yet he gave them all the respect they deserved. Indeed, he became known in later life as Kid Cement more as a reference to his toughness, hardness, and uncompromising batsmanship than anything else. Freddo started playing cricket when there were no helmets worn by anyone at all, yet only late in his cricketing life, about 1978, during Kerry Packer’s World Series Cricket, did he actually wear one.

It was suggested that seldom did he allow the ball to get close to his head, so good was his eyesight, so great were his foot movements, and so ferocious were his cutting, pulling, and hooking—three wonderful cricket shots that are almost extinct these days in the modern cricket game. Just before Gordon Greenidge and Desmond Haynes became a cricketing item, as openers, there had been Gordon Greenidge and Roy Fredericks. Indeed, Fredericks was actually before Greenidge, as Freddo started his Test career in 1968 against the Australians.

Gordon Greenidge only started his career in 1973 in India. Frederick played his last series and his last Test, with me included, for the first time in the West Indies cricket team against Pakistan in 1976–77. He even made a glorious century in the second Test of that, his last series at Port of Spain, my second Test. The fact that he was not Man of the Match of that game was due only to the fact that I somehow managed to get my best Test figures in Pakistan’s first innings, 8 for 29.

Roy Fredericks hooked, cut, slashed, bludgeoned, gored, scythed, thrust, drove, parried, and perhaps drew and quartered the world’s best bowling attack in 1975–76, as they had never been before or since. To this day, that innings of 169 against Australia at Perth, then lightning fast—the fastest pitch in the world, much faster than it is now—is talked about by all who either witnessed it or read about it.

Heard it on radios, or saw it on television. It is perhaps one of the best innings, if not indeed the best, ever played by an opening batsman in defiance of all around him, with his very life dangling in front of him at all times, with deliveries clocked in the old way at over 100 miles per hour.

On the cricket field, Fredericks always flew in the face of everything that came at him, totally uncompromising in his fight for runs for whichever team he was playing for. Even the last time, I saw Freddo he was still concerned about the lack of real batsman-ship in today’s West Indies cricket team, the real guts to play the game at the highest level.

He probably would have been embarrassed to have seen Wavell Hinds, Shivnarine Chanderpaul, and Brian Lara, all of his left-handed ilk, duck weave, flinch, squirm and generally be ill at ease in the second Test at Lord’s as the English fast-bowlers dug deliveries into the daringly lively pitch, resulting in the projectile getting into the rib areas of the batsmen.

I guarantee that Freddo would have lashed the bowlers so hard and so far, perhaps as far as Marble Arch, that they would have had to try something else to get him out. They certainly would have had to find new balls, in every way, to bowl with. Yes, Freddo was indeed a tough champion, and many of us who had been his friends and his teammates are going to miss him.

Roy Fredericks Death

Roy Fredericks was 57 when he died of throat cancer in New York on September 5, 2000. amid glowing tributes from politicians and Caribbean cricket greats. It is a sad day for West Indies cricket, said David Holford, a former teammate of Frederick’s and former West Indies chief selector.